Which way farm animal welfare in Tanzania?

Summary

Tanzania is one of the world’s poorest and least developed countries but has huge numbers of cattle, goats, sheep and poultry, fewer pigs and very few water buffalo and camels.

Most animals are kept under low input-low output conditions in mixed crop-livestock, pastoral or urban and suburban farming systems. Producers are usually poor, have limited access to resources and struggle to ensure their own livelihoods.

An Animal Welfare Act was brought on to the Statute Book in 2008: its provisions are based on similar legislation in developed countries and, together with ancillary legal instruments, lays the foundation for farm (and companion) animal welfare.

Welfare is poor at all stages of the value chain from producer, through transport and marketing to slaughter.

Most producers are unaware of good wel- fare practices. During transport and at slaughter welfare is ignored by those responsible for it including government personnel charged with ensuring welfare and food safety.

Government is less than strict in overseeing application of the law and there is very little pressure from consumers or others to ensure even minimum compliance with appropri- ate standards.

Two voluntary associations attempt to improve the welfare of dogs, cats and donkeys but none is concerned with farm animals. Under these scenarios the prognosis for improved farm animal welfare in Tanzania in the foreseeable future is bleak.

Keywords: animal welfare, animal transport, legislation, pain, slaughter, stress.

Introduction

“Unseen they suffer Unheard they cry In agony they linger In silence they die

Is it nothing to all ye who pass by?”

The Lord Buddha (attributed, although also claimed by some animal rights’ movements)

Since the Republic of Sudan split to become two separate countries in 2012, Tanzania is second only to Ethiopia in the number of its domestic livestock. Its standing stock is estimated to comprise 21.3 million cattle, 13.1 million goats 3.6 million sheep, 1.5 million pigs and more than 30 million poultry (1).

More than 99 per cent of these animals are owned and managed by resource-poor smallholder mixed and pastoral producers operating in an age-old traditional manner and by slightly more intensive urban and suburban systems.

Livestock provide direct livelihood support to 4 901 837 agricultural households (2). The human population of 46.2 million lives in a low income country whose Gross Domestic product is US$ 23.71 billion or about US$ 510 per person per year.

The human development index ranks 152 in a league table of 187 with comparable data (3) meaning that not only is income low but also that life expectancy, education, access to health and a range of other indicators are also poor.

Few rural households have access to electricity. Water for drinking, washing and cooking usually has to be fetched (and usually on the heads of women) from several kilometres away. Very few houses have toilets or latrines.

Livestock are owned by families in two major systems. Mixed crop- livestock farmers and agropastoralists keep few ruminants, up to about 20 head but often fewer, close to the homestead and these may be tethered or roam freely during the day and brought in to a pen at night.

Pastoralists have ruminant herds of up to 100 head, that are herded on open range during the day and closeted in a thorn enclosure at night.

In rural areas pigs usually roam freely during the day but are housed at night (4) whereas in urban and suburban areas they are fully confined (5). Poultry are free range and scavenge for most of their food in both rural and urban areas (6).

Most livestock, but especially ruminants, are hungry from their birth to their death (7). Calves, kids and lambs are separated from their dams for part of every day and are even denied colostrum so that dams can be milked to provide food for people.

Feed, mostly natural pasture and crop residues such as straw, is insufficient in quantity and quality for most of every year to provide adequate nutrition for growth and inhibits the reproductive process (2).

Water is often in very short supply and pastoral livestock in particular may go several days without drinking.

The chain of events for livestock from pasture to plate can be summarized as a growth period of inadequate feed resources, transfer to a primary market for sale, purchase by an agent and transfer to a secondary market for resale, purchase by a butcher or other intermediary, slaughter under usually primitive and unhygienic conditions and final transfer to a retail sale point.

Materials and methods

This paper is based mainly on empirical observations throughout the Tanzanian livestock sector over the years 1961 to 2013 but especially during three visits, each of about 30 days duration, to Tanzania from September 2012 to February 2013.

Observations, which have been combined with interviews and informal discussions with key informants, were made in all production systems and during visits to livestock markets, on transport routes and at informal and regulated slaughter slabs and abattoirs.

Welfare concerns and clear breaches of the Animal Welfare Act are illustrated in this paper by a series of photographs.

Observations have been supplemented with a review of animal welfare legislation in Tanzania and of general and Tanzania publications on animal welfare: it should be noted, however, that literature for Tanzania is extremely scanty.

Results

Legislation and the role of Government

The livestock sector is beset by a plethora of laws, rules and regulations related to production, health and disease, food quality and safety and welfare. Implementation of this corpus may be in concert, but is often in conflict, with other legal instruments.

Direct and indirect legislation is enforced and implemented (or not enforced and not implemented) by various ministries, institutions, boards, authorities and local governments.

Tanzania is widely regarded as having a theoretically dense regulatory burden that is lightly implemented and widely ignored (8). To add to earlier regulation much that is new has been enacted since 2003, amongst which are:

Act No 16 of 2003: An Act to provide for the registration of veterinarians, or enlistment of Paraprofessional and Paraprofessional Assistants, and for the establishment of the Veterinary Council and other matters incidental and connected thereto (“The Veterinary Act”);

Act No 17 of 2003: An Act to make provisions for control and prevention of animal diseases for monitoring production of animal products, for disposal of animal carcases and for other related matters (“Animal Diseases Act”);

Act No 10 of 2006: An Act to make provisions for the restructuring of the Meat Industry, to establish a proper basis for its efficient management, to ensure provision of high quality meat products and for matters related therewith. (“The Meat Industry Act”);

Act No 13 of 2010: An Act to provide for the management and control of grazing-lands, animal feed resources and trade and to provide for other related matters (“Grazing Land and Animal Feed Resources Act”);

Act No 12 of 2010: An Act to provide for the establishment of the National Livestock Identification, Registration and Traceability System for purposes of controlling animal diseases and livestock theft, enhancing food safety assurance; to regulate movement of livestock, improve livestock products and production of animal genetic resources; to promote access to market and to provide for other related matters (“The Livestock Identification, Registration and Traceability Act”);

and, most relevant of all:

Act No 19 of 2008: An act to provide for the humane treatment of animals, establishment of the Animal Welfare Advisory Council, monitoring and mitigation of animal abuses, promoting awareness on the importance of animal welfare and to provide for other related matters (“Animal Welfare Act”).

Amongst the major chapters of the Animal Welfare Act (9) – which supercedes the Animal Protection Ordinance Cap 153 of the pre- Independence period – are:

* Establishment of the Animal Welfare Advisory Council;

* Keeping of animals (farm animals, companion animals, transport, care of injured animals, slaughter);

* Use for work and entertainment; I Surgical operations, biotechnology and experiments; and

* Control of aggressive animals and animal pound.

Subsidiary regulation to the foregoing includes principally:

* Tanzania Bureau of Standard’s Code No TZS 128: 1981(E) Meat and meat products;

* The Meat Slaughter Regulations;

* The Meat Hygiene Regulations;

and

* Guidelines for Slaughter Facilities of the Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority.

Under the chapter ‘Keeping of animals’ of the Animal Welfare Act, prominence, with regard to farm animals, is given to appropriate housing, not causing pain or suffering, minimum standards for transport vehicles, not overworking or overloading animals used for work and transport and providing them with “shade, shelter, a soft lying space and adequate space for relaxation during rest periods” (Sections 33 ‘Duty of care to a working animal’ and 34 ‘Working animals not to be overworked’).

With regard to slaughter (Section 29 ‘Humane slaughtering’), “an animal shall be slaughtered through a method which (a) involves instantaneous killing, or (b) instantaneously renders an animal unconscious and ends in death without the recover [sic] of consciousness”.

Slaughtering methods that may be used for ruminants and pigs are “(a) mechanical means of employing an instrument which administer a blow or penetrate the brain, or (b) electronarcosis”.

The provisions of this part of the Act shall not apply (Section 30 ‘Approval of religious slaughter’) where religious beliefs specify the mode of slaughtering provided that (a) the person doing the slaughtering has the necessary knowledge and skill, (b) a veterinarian in charge of slaughter and meat inspection must be present, ( c) the large blood vessels of the throat must be opened with a single cut, (d) equipment is available such that the animal intended for slaughtering can be brought into position without delay, and (e) other animals awaiting slaughter must not see the process.

Slaughter of pregnant animals is discouraged and ante-mortem inspection for pregnancy is required.

Welfare in practice

The five freedoms (10, 11, 12) are amply covered under Tanzania’s enacted legislation.

Practice, however, is remote from principle. In the Tanzania context there are three major stages in an animal’s life. The first is production, the second transport and marketing and the third slaughter.

There is little second order production (an animal being sold from its place of origin to another producer for growing on or fattening) so stages two and three are usually compressed in time although not necessarily in space.

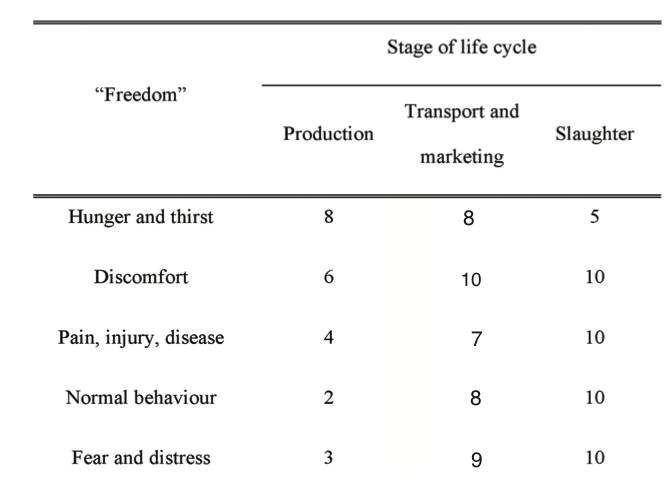

Animals encounter welfare problems – although in this study these have of necessity been assessed with some subjectivity as physical and physiological tests described by some authors (e.g. 13) were not possible – which in order of magnitude rise from mild to very severe (Table 1).

Production on the farm and in the pastoral areas

For Tanzanian livestock, welfare problems begin in the womb, a part of the life cycle which until recently has had little attention given to it in relation to later welfare, health and production (14).

The developing foetus, especially the ruminant one, is deprived of adequate nutrition and open to infection as its dam is rarely herself protected against diseases which may be transmitted through the uterus.

The newborn is thus underweight at birth, weak and open to attack by parasites and pathogens.

The situation does not improve at birth. Ruminant young are often given limited or even no access to colostrum and are deprived of protective antibodies.

They continue to suffer stress in the post-natal/pre-weaning period as they compete with their owners for their dams’ milk and are separated from the latter for long periods to prevent suckling.

Stress and starvation result in very slow growth and high mortality rates, in Tanzania as in other African traditional systems (15, 16, 17).

Hunger and thirst continue throughout the slow growth process to maturity as animals rarely obtain a diet sufficient to maintain full health and vigour and often have no ready access to fresh water (18).

Most animals receive little health care (only 29 per cent of cattle are vaccinated regularly), protection from ticks (and the diseases they carry) or control of internal helminth parasites (2).

Consequently, if the animal does not succumb to its miserable life style (death rates are very high in calves and may reach 70 per cent of those infected by East Coast Fever (ECF) which can be reduced to less than 30 per cent with regular dipping), reproductive rates in cattle are only about 50 per cent (a cow calves first at 4 or even 5 years of age and then produces a calf only every 2 years) (2, 19).

Growth is slow (and characterized by the typical saw-tooth gain-loss-gain annual cycle, (20)) as a result of feed shortages for most of every year (Figure 1) and extended intervals, of up to four days, between successive waterings.

Pigs managed under free-range or near-free range conditions (about 70 per cent of pigs in Tanzania (21)) have better access to feed than ruminants as they scavenge a wide range of foods and household waste, including the large quantities of human excrement around villages where latrines are not used.

Urban pigs under confinement usually receive adequate amounts of food although much of this is unbalanced for nutrients, especially minerals and vitamins (pers. obs.). Access to water remains problematic for pigs and poultry and especially for the latter in the long dry seasons.

Freedom of their animals from discomfort is not a priority for most Tanzanian producers.

Shelters are often rudimentary and comfortable resting areas are not widespread. In pastoral areas, stock is penned at night in some kind of enclosure of thorns, of wooden offcuts or of posts and barbed wire.

Young stock are crowded into a smaller version of the main pen and separated from their dams to prevent suckling. Pens (’boma’ in local languages) are thick with the dust that results from thousands of hooves trampling the dung during the long dry periods or hock deep in liquid manure in the wet season when no dry spot is to be found (18).

No bedding is provided and there is seldom any shade. In the smaller crossbred dairy units housing hygiene is often poor or very poor with inadequate drainage, pot-holed flat floors and dung and waste materials are often disposed of nearby which only exacerbates the unhygienic conditions (17).

In mixed agricultural units and in urban areas (most municipalities have by-laws that require animals to be totally and permanently confined) ruminants are sometimes housed in the family home or an attached lean-to or in a primitive pen close at hand but, although this may have a corrugated iron or thatched roof, there are appalling conditions underfoot and there is rarely any drainage (22).

Both rural and urban pigs are usually housed in crude pens with earth or rough concrete floors that do not drain well, have no bedding and no separate defecating area.

In the small scale system in Dar es Salaam pens are closely crowded and a potential source of epidemic disease (Figure 2). Recently built – “modern” – large scale facilities start off with the use of farrowing crates (Figure 3).

Disease prevention and rapid diagnosis and treatment are not realities in Tanzania and stock is consequently not free from disease nor pain. In most situations the only regular animal health treatment is dipping or spraying for tick control to inhibit development of tick-borne diseases (23) but animals suffer pain, fear and distress as they are shouted at and beaten to drive them through often poorly designed facilities.

Many animals, especially in more extensive systems, have sufficient space and the company of others of their own kind and thus have some freedom to express normal behaviour. The major exceptions to this rule are intensive units and urban dairy and pig units.

Transport and marketing

The first steps in the ruminant marketing chain usually comprise sale off the producer holding and movement on foot to one of 300 primary markets.

This is followed by purchase by an agent for transfer to a secondary market of which one is located in Dar es Salaam and the others in the north of the country (24).

The law requires that animals be transported by truck to a secondary market. Most stock does, in fact, arrive at such a market in a truck but only after it has been loaded a short distance from the market after a trek that may have lasted several weeks over a distance of several hundred kilometres.

Several points along the marketing chain provide opportunities for welfare to be severely compromised. Gathering at markets mixes animals strange to each other and exposes them to disease.

During trekking animals pass weeks without adequate feed and only intermittent access to water. Neither of the two separate railway systems in Tanzania operates regularly and neither has rolling stock for animal transport.

Specialized road transport vehicles for livestock are unknown so where road transport is used (often as a back-load to Dar es Salaam from remote parts of the country) the vehicle is not adapted -- by any rational interpretation – for animals (24).

There are welfare problems at loading from unsuitable ramps (or from no ramp at all), throughout journeys that may be of several days duration (Figure 4) and at unloading.

A variety of transport methods is used by the small holder mixed farmer to get his animals to market. Trekking is one option but transport by road is often preferred especially if the distance is greater than 20 km (Figure 5).

A common method of moving pigs from the point of production to market is driving them on foot but more imaginative methods – with less welfare concern – are often used (Figure 6). Indigenous poultry are raised usually in small flocks at household level.

Markets are usually too far away for a householder to deliver them to market so a small scale dealer constitutes lots and transports them by bicycle in baskets of bamboo stems containing up to 50 or more birds (Figure 7).

Conditions do not improve for animals at the market. At the few with some infrastructure (other than a boundary wall) it is usually poorly designed, constructed and maintained.

Square angles inhibit free movement of animals and projecting crude metal including over-long bolts encourage injury. Welfare is compromised by the resultant beating to get animals moving.

The bruising that ensues (25) would result in financial loss if meat were condemned but neither inspectors nor consumers regard bruising as a reason for rejection.

Slaughter

The Animal Welfare Act is unequivocal with regard to humane and correct slaughter.

With very few exceptions, nowhere along the chain – from slaughter in the producer’s backyard to slaughter in a modern export abattoir – is humane and correct slaughter performed.

The several hundred rural slaughter slabs are just that – a slab of concrete a few metres square in the better ones but with no other facilities or equipment.

These are largely unregulated although a meat inspector may occasionally be present. At the 100 or so municipal slaughter houses the situation is little better.

Most of these are many years beyond their “use by” date but slaughter up to five times their design capacity.

They have little equipment, inappropriate and broken lairage and lack handling and restraint facilities (Figure 8) such that animals are lassoed in a rodeo performance before being thrown to the ground and having their throats cut with one stroke if they are lucky.

Rarely is the final act carried out beyond the sight, sound and smell of their fellow animals awaiting the same fate (Figure 9). Even where electric stunning is available it is usually deemed easier to slaughter without the animal first being rendered unconscious (Figure 10).

It is easy to make a case for “religious slaughter” for ruminants but none such can be made for pigs. It is unlikely, nonetheless, that any pig is slaughtered in Tanzania after being rendered unconscious.

Many pigs are slaughtered under uncontrolled conditions at the home but even where a meat inspector is called in (as at the pig “farm” in Figure 2) animals are not stunned (26, 27) although meat inspectors are also welfare officers.

Discussion

Consideration for animals and their well-being within the food chain is the responsibility of stakeholders at all levels from primary producer to final consumer (28).

The Animal Welfare Act 2008 imposes, as does the New Zealand Act of the same name of 1999 (29), a duty of care on all owners and persons in charge, to provide for the physical, health and behavioural needs of animals in their care.

In developed countries producers make provision for good welfare through good husbandry.

Unlike New Zealand and other developed countries, however, it is far from easy in a developing country such as Tanzania to integrate, at producer level, the various and often conflicting, social, ethical and economic conditions into the livestock production chain when people themselves live in a miserable and unhealthy state and know little of nor understand the meaning of “welfare” and appreciate it even less.

Along the chain, during transport and at slaughter, responsibility for welfare shifts incrementally from producers to local and central government and their employees who have received some technical training and who are in general aware of the regulations of the Welfare Act 2008.

It is at these points, however, that the worst welfare examples are manifest not only with respect to the law but also to feelings of compassion for unnecessary and needless suffering.

Government has enacted the necessary legislation but neither it (at central or local level), its technical agencies nor its agents attempt to see the law applied either through lack of diligence or – worse – through receipt of “facilitation fees” (the World Economic Forum Competitiveness Report (8) ranks Tanzania at 120 out of 142 countries with a major reason for this position being corruption) to allow the law to be flouted.

At the end of the chain the average Tanzanian consumer has little disposable income, eats meat on limited occasions only and is more concerned with price than with the processes an animal has been through before meat is put on the plate.

It is unlikely in the near future that consumers will wish to attempt to influence the forces that drive the market even though livestock make a major contribution to their well being.

Nor will they understand that improved farm animal welfare can improve productivity and food safety and provide economic benefits.

There are, however, some encouraging, if very limited, indications that animal welfare is becoming of concern.

The Tanzania Animal Welfare Society (TAWESO), whose current activities are with stray dogs and cats in Dar es Salaam but which has plans for a donkey sanctuary in Dodoma, was formed in 2008.

The mission of the Tanzania Animals Protection Organization (TAPO) is “to protect all Animals from Tortures, Cruelty, Abused, Diseases and killings in the country of Tanzania” and whose vision is that “All Animals shall be respected as living beings like human beings” but its activities mainly relate to donkeys.

TAPO is a member of the World Society for the Protection of Animals and the Equine Welfare Alliance of the USA but its activities, as those of TAWESO, are limited as they rely on public donations because “the government does not support financially the non-profit organizations in the country” (http://www.taweso.org/).

Tanzania is not alone in Africa in having NGOs concerned with animal welfare but even in the most advanced African countries the current emphasis – because of financial constraints and to capture a public audience – is also on companion animals and the donkey (30, 31).

Tanzania is a member country of the World Organization for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties, OIE), the intergovernmental organization founded in 1924 to set global rules for monitoring, prevention and control of animal diseases.

In 2001 OIE formally extended its work to include animal welfare and in 2005 adopted the first global standards including, of relevance to Tanzania, welfare during transport by land and sea (Tanzania exports live animals to its offshore region of Zanzibar and to the Comores Islands in the Indian Ocean) and welfare during slaughter for human consumption as well as for disease control.

The standards define the responsibilities and competence required of workers, good practice in handling and slaughter, requirements for welfare during transport and lists practices that are unacceptable. None of these standards is yet adhered to in Tanzania.

Few animals and small quantities of meat are exported from Tanzania. Most trade is to countries in the eastern and southern African region and the Arabian Gulf including predominantly the United Arab Emirates.

None of these countries demands high welfare standards throughout the chain as a condition for import but some, at least, may do so in the medium term.

Animal welfare considerations

The Tanzanian Government pays lip service to farm animal welfare through its Animal Welfare Act of 2008 but makes very little attempt to enforce the Act’s provisions.

As far as can be ascertained there has yet to be a prosecution for breaches of the law. Producers, transporters, butchers and consumers alike have little knowledge of or interest in the welfare of animals, partly through ignorance and lack of education but also because their own welfare standards are wanting.

Under these scenarios the prospects for improving farm animal welfare in Tanzania will remain bleak for a long time to come.

No country to which Tanzania exports, at present, demands high welfare standards, as a condition for import, but some, at least, may do so in the medium term.

Acknowledgements

In memoriam, Professor Sir Colin Spedding, respected mentor, valued colleague and formidable protagonist of animal welfare everywhere.

References

1) FAOStat (2012) FAO Statistical Year Book 2012. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome. http://faostat3.fao.org/home/index.html. Accessed 15 04 2013.

(2) Covarrubias, K, Nsiima, L & Zezza A (2010) Livestock and livelihoods in rural Tanzania: A descriptive analysis of the 2009 National Panel Survey. Washington DC, World Bank.

(3) UNDP (2012) Human Development Report. Nairobi, United Nations Development Programme.

(4) Ngowi, H A, Kassuku, A A, Maeda, G E, Boa, M E, Carabin, H & Willingham A L III (2004) Risk factors for the prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Veterinary Parasitology 120, 275-83

(5) Munisi, W, Sambuta, A, Bwire, J & Meho, A (2006) Pig production in peri-urban areas of Mpwapwa district, Tanzania: Current situation, constraints and improvement options. Proceedings of the 32nd Scientific Conference of Tanzania Society of Animal Production 32, 125-8.

(6) Msoffe, P L M, Bunn, D, Muhairwa, A P, Mtambo, M M A, Mwamhehe, H, Msago, A, Mlozi M R S & Cardona, C J (2010) Implementing poultry vaccination and biosecurity at the village level in Tanzania: a social strategy to promote health in free-range poultry populations. Tropical Animal Health and Production 42, 253-63.

(7) Rushalaza, V G & Kasonta, J S (1993) Dual- purpose cattle in central Tanzania. In: Future of livestock industries in East and southern Africa. Proceedings of a workshop held 20-23 July 1992 at Kadoma Ranch Hotel, Zimbabwe (ed., A. Kategile & S. Mubi), International Livestock Centre for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp. 81-8.

(8) World Economic Forum (2011) The Global Competitiveness Report 2011-2012. Geneva, World Economic Forum.

(9) URT (2008) Act No 19 of 2008: An act to provide for the humane treatment of animals, establishment of the Animal Welfare Advisory Council, monitoring and mitigation of animal abuses, promoting awareness on the importance of animal welfare and to provide for other related matters (“Animal Welfare Act”). Dar es Salaam, Government Printer.

(10) Brambell, F W R (1965) Report of the Technical Committee to enquire into the welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems [“The Brambell Report”]. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

(11) Fraser, A F &nd Broom, D M (1997) Farm animal behaviour and welfare. London, CAB International.

(12) Rushen, J (2008) Farm animal welfare since the Brambell report. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 113, 277-8.

(13) Broom, D M (1991) Animal welfare: concepts and measurement. Journal of Animal Science 69: 4167-75.

(14) Rutherford, K M D, Donald, R D, Arnott, G, Rooke, J A, Dixon, L, Mehers, J J M, Turnbull, J & Lawrence, A B (2012) Farm animal welfare: assessing risks attributable to the prenatal environment. Animal Welfare 21, 419-29.

(15) Wilson, R T, Traoré, A, Peacock, C P & Mack, S (1984) Mortalité avant le sevrage dans les systèmes africains traditionnels d’élevage des caprins. In: Les maladies de la chèvre (Colloques de l’INRA No 28) (ed., P. Yvore & G. Perrin). Maisons-Alfort, Institut d’Elevage et de Médicine Vétérinaire des Pays Tropicaux. pp. 665-72.

(16) de Leeuw, P N & Wilson, R T (1987) Comparative productivity of indigenous cattle under traditional management in subSaharan Africa. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture 26, 377-90.

(17) Chang’a, J S, Mdegela, R H, Ryoba, R, Løken, T & Reksen, M (2010) Calf health and management in smallholder dairy farms in Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production 42, 1669–76.

(18) Msanga, Y N, Mwakilembe, P L & Sendalo, D (2012) The indigenous cattle of the Southern Highlands of Tanzania: distinct phenotypic features, performance and uses. Livestock Research for Rural Development Volume 24, Article #110. Retrieved March 11, 2013, from http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd24/7/msan24110.htm

(19) Pica-Ciamarra, U, Baker, D, Chassama, J, Fadiga, M & Nsiima, L (2011) Linking Smallholders to Livestock Markets: Combining Market and Household Survey Data in Tanzania. Paper presented at the 4th Meeting of the Wye City Group on Statistics on Rural Development and Agriculture Household Income, 9-11 November 2011, Rio de Janeiro.

(20) Wilson, R T (1986) Livestock production in central Mali: Long-term studies on cattle and small ruminants in the agropastoral system (Research Report No 14). Addis Ababa, International Livestock Centre for Africa. p. 54, 93.

(21) Ngowi, H A, Carabin, H, Kassuku, A A, Mlozi, M R S, Mlangwa, J E D and Willingham, A L III (2008) A health-education intervention trial to reduce porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 85, 52-67.

(22) Mvena,ZSK,Lupanga,IJ&Mlozi,MR S (1991) Urban agriculture in Tanzania: a study of six towns (Research Report). Ottawa, International Development Research Centre.

(23) Ogden, N H, Swai, E, Beauchamp, G, Karimuribo, E, Fitzpatrick, J L, Bryant, M J, Kambarage, D & French, N P (2005) Risk factors for tick attachment to smallholder dairy cattle in Tanzania. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 67, 157-70.

(24) UNIDO (2012) Tanzania’s Red Meat Value Chain: A diagnostic (Africa Agribusiness and Agroindustry Development Initiative (3ADI) Reports). Vienna, United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

(25) Weeks, C A, McNally, P W & Warriss, P D (2002) Influence of the design of facilities at auction markets and animal handling procedures on bruising in cattle. Veterinary Record 150, 743-8.

(26) Mdegela, R H, Laurence, K, Jacob, P & Nonga, H E (2011) Occurrences of thermophilic Campylobacter in pigs slaughtered at Morogoro slaughter slabs, Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production 43, 83-7.

(27) Mkupasi, E M, Ngowi, H A & Nonga, H E (2011) Prevalence of extra-intestinal porcine helminth infections and assessment of sanitary conditions of pig slaughter slabs in Dar es Salaam city, Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production 43, 417-23.

(28) Webster, A J F (2001) Farm animal welfare: the Five Freedoms and the free market. Veterinary Journal 161, 229-37.

(29) O'Connor, C E & Bayvel, A C D (2012) Challenges to implementing animal welfare standards in New Zealand. Animal Welfare 21, 397-401.

(30) Masiga, W N & Munyia S J M (2005) Global perspectives on animal welfare: Africa. OIE Review of Science and Technology 24, 579-86.

(31) Wilkins, D B, Houseman, C, Allan, R, Appleby, M C & Peeling, D (“005) Animal welfare: the role of non-governmental organisations. OIE Review of Science and Technology 24, 625-38.

Download pdfFigures

Table 1. Severity of welfare problems related to the five freedoms encountered by Tanzanian livestock at three stages of the life cycle. Initial parenthesis assessed by the author on a scale 1 = mild or mini- mal, 10 = very severe).

Figure 1. Natural feed resources for cattle in central Tanzania (part of a parastatal ranch where the stocking rate is clearly not adjusted to the carrying capacity).

Figure 2. Small scale urban pig production in Dar es Salaam (note primitive drainage system and method of emptying by hand; the building in the background is a block of flats for police personnel who rear pigs to supplement their meagre incomes).

Figure 3. A modern pig breeding facility in Dar es Salaam with farrow- ing crates (the enterprise is part funded by Danish Technical Assistance: under European Union law, Denmark was due to phase out the use of farrowing crates in 2012).

Figure 4. Cattle being transported by road from Sumbawanga to Dar es Salaam (more than 50 cattle loaded on a general-purpose truck with no partitions and being beaten to force the ones lying down to stand: the time for the 1426 km journey – much over unmade dirt track – is said to take 18 hours and 34 minutes by car but by lorry requires at least three days during which time the animals are neither fed nor watered).

Figure 5. Two native cattle being transported to market in Morogoro in east-central Tanzania by pick-up truck.

Figure 6. A pig on its way to market in Sumbawanga.

Figure 7. A dealer lot of poultry on its way to market left in the sun whilst their owner takes a rest in the shade.

Figure 8. A privately owned slaughter house within the greater Dar es Salaam conurba- tion (note the broken “crush” to the left and the concrete tank in the centre for disposal of con- demned animals and meat: all such facilities are approved by the Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority and the Municipal Council and veterinarians or vet- erinary assistants attend for ante- mortem live animal inspection and postmortem meat inspec- tion).

Figure 9. The charnal house at the publicly-owned Vingunguti slaughter facility of Ilala Municipality in greater Dar es Salaam (goats are killed in full sight, sound and smell of their fellow animals awaiting the same fate).

Figure 10. Slaughtering goats for export to UAE without stunning at Dodoma abattoir (the abattoir has electric stunning facilities and has no problems exporting cattle carcasses stunned before exsanguination to the Islamic Gulf States).